Teaching games for understanding (TGfU) is understood as problem-based approach to games teaching where the play of a game is taught to situated skill development. The TGfU approach has encouraged debate on games teaching which until recently has often polarized into skills v tactics arguments. In reality it is. Understanding the future is critical to make the right decision. Despite that understanding traditional strategy is backward-looking, often building on historic financial data and market performance to extrapolate future trends. Finally, one of the specs of the traditional strategy process is its frequency.

There are several big movements underway that are worthy of debate and possible consideration as we look to help education become the 21st century, user-centered, on-demand, engaging, technology-centric activity that it has not been for much of its existence. Game-based learning (GBL), or gamification, is one of the models that commonly gets touted as a cure-all for the problems with education because of the popularity of gaming in our society (New Media Institute). While there are problems with the gamification movement as it currently stands, the model has several areas in which it differs sufficiently from traditional education to make it an intriguing possibility. Here is a look at several of those differences.

Authenticity

This is one of the most interesting and controversial areas where GBL can separate itself from what we see in the traditional classroom. In fact, GBL has two distinct advantages over even project-based learning, which is generally considered to be among the most authentic situations for classroom learning (Stepien & Gallagher). PBL relies on students working on less-than-authentic problems regardless of the intent. One simply cannot engage in an authentic learning exercise in a classroom…unless you can enter a virtual world within the classroom.

Games have the potential to allow students to do exactly that. The entire premise behind games is that they allow those playing them to experience simulations of reality that can replicate real world circumstances, and theoretically can elicit the same emotional and learning responses in the brain as actually doing the real activity.

The second point is that, while it is becoming increasingly possible for students, particularly in higher education, to use authentic professional tools, it is still not the norm. While those playing games and doing simulations may not be using real tools for the task they are engaging in, they can use realistic analogs within the game and are using authentic tools to play the game. There is an inherent value in any computer use that transfers to the everyday and professional activities that people do. From the physical activity of using a mouse, keyboard, or gesture-based controller, to developing familiarity with operating systems, and using a wide array of applications, students who use technology more and engage more deeply with it have an advantage when it comes to developing technological literacy (Marquis, 2009).

While it is true that educational games often lack much of the engagement and fidelity of commercial games, and commercial games generally fall short on intellectual content, there is a middle ground where the two camps can meet and work together to develop powerful and engaging educational games that will accomplish the objectives stated here.

Student Engagement

The hidden agenda of games and play is to teach. This is why animals play and why we encourage our youngest children to play games. So that they develop an understanding of the world around them and the social relationships that they will need to engage in to be successful members of their group. Games are also fun. That is the reason that we like to play. Formal games with rules serve the same functions, but additionally motivate us through our competitive nature. For all of these reasons, GBL works to engage students in ways that are more powerful for most students than traditional teaching methods, which, while effective, present obstacles to engaging deeply with each individual student.

Some teachers do an outstanding job of engaging their students to the extent that the traditional classroom format allows. However, seldom if ever do you see students in a non-game-based classroom experiencing what game designer Jane McGonigal calls 'blissful productivity' – deriving enjoyment from working hard to overcome obstacles. During game play, the individual is optimizing their productivity and enjoying it. People playing games also report losing track of time in the real world. This phenomenon is due to the extreme level of engagement that some games can promote in those playing them. This is a sharp contrast to the usual school situation where everyone, often including the teacher, is watching the clock, waiting for the school day to end.

Creativity and Innovative Thinking

The final area in which GBL can be superior to traditional classroom learning is in fostering creativity and teaching students to be innovators. While it is not impossible for the traditional classroom model to inspire students to be creative, the standards-based approach to education, particularly in K-12 schools, works in direct opposition to this goal. A standardized curriculum, with results evaluated by standardized test cannot support individuality and actively discourages students from thinking outside the box.

Even in higher education, where one of the main goals of the university system is innovation, actual classroom teaching at the undergraduate level is largely intended to produce students who fit the needs of industry, rather than creative individuals who define industry itself. Those who break out of this mold to create new products, services, and markets are a very small percentage of actual college graduates – they are the exception rather than the rule.

The argument against GBL supporting innovation is obvious – playing games is also working within a standard set of rules, often in a nearly linear progression. A true enough assessment of many educational games and some of the less innovative commercial games, but the best games not only allow creativity and randomness (it is generally programmed into games), but demand it. One commercial game in particular that has some demonstrated educational success comes to mind: Civilization.

Civilization is one of the best examples of the ways in which an extremely popular commercial game can be used for educational purposes. The game allows players to manage the rise of specific civilizations. They are in control of many of the variables that govern success or failure of the groups being controlled. Where Civilization becomes important in this discussion is in the proliferation of user generated content that has been created for it. Thousands of players have been collaborating for more than a decade to develop game mods that accurately represent real world civilizations. Through these mods users can attempt to replicate the rise of the Roman Empire, or almost any other historical civilization. They work together on the Apolyton University site where they share suggestions for new mods and collaborate on creating them.

Cost

One area in which GBL is surpassed by traditional classroom learning is cost. GBL requires that each student have access to computers or other gaming devices for a far greater percentage of their instructional time than is generally possible in schools. Even at the university level, a vast majority of classrooms do not have adequate computers to allow for students to engage in GBL. Providing that kind of access is a monetarily daunting task. In addition to the cost of equipment, games themselves can be expensive to purchase. There are not generally site license options for commercial games, and while there are many free games available, aligning them to instructional needs is a challenge.

GBL is, however a best-case-scenario and there is no reason to disregard it because of the potential cost of implementation. Every new innovation and technological advance requires an investment of time, thought, and money. In fact, a concerted shift to GBL might prompt funding increases for education that would benefit students in every aspect of their education. Certainly sticking with a traditional curriculum is more efficient and saves money, but neither of those things are actually beneficial to education.

The Debate Goes On

One of the biggest problems with GBL is that we are not ready for it yet. Students are ready – they spend vast amounts of time playing games and interacting in virtual worlds – but teachers, parents, politicians, and the gaming industry are not ready. Schools lack the infrastructure to support large-scale gamification, teachers lack training in the pedagogy of GBL, parents do not see the value of games, politicians view education as a burden that should be more efficient and cost effective, not less, and the gaming industry focuses almost exclusively on non-educational content. We have a long way to go before GBL can become a reality for most students.

One way to spark this change is for educators, parents, and politicians to put pressure on the gaming industry to focus on shifting game content towards areas which can be readily incorporated into education. This is an ongoing debate and your input into the discussion is valued and encouraged. Contribute your opinion on Google+ or Twitter @drjwmarquis using the tags #gamification, #GBL, or #GBLFriday.

Image: FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Cite this guide: Bowen, Ryan S., (2017). Understanding by Design. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [todaysdate] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/understanding-by-design/. |

Overview

Understanding by Design is a book written by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe that offers a framework for designing courses and content units called “Backward Design.” Instructors typically approach course design in a “forward design” manner, meaning they consider the learning activities (how to teach the content), develop assessments around their learning activities, then attempt to draw connections to the learning goals of the course. In contrast, the backward design approach has instructors consider the learning goals of the course first. These learning goals embody the knowledge and skills instructors want their students to have learned when they leave the course. Once the learning goals have been established, the second stage involves consideration of assessment. The backward design framework suggests that instructors should consider these overarching learning goals and how students will be assessed prior to consideration of how to teach the content. For this reason, backward design is considered a much more intentional approach to course design than traditional methods of design.

This teaching guide will explain the benefits of incorporating backward design. Then it will elaborate on the three stages that backward design encompasses. Finally, an overview of a backward design template is provided with links to blank template pages for convenience.

The Benefits of Using Backward Design

“Our lessons, units, and courses should be logically inferred from the results sought, not derived from the methods, books, and activities with which we are most comfortable. Curriculum should lay out the most effective ways of achieving specific results… in short, the best designs derive backward from the learnings sought.”

In Understanding by Design, Wiggins and McTighe argue that backward design is focused primarily on student learning and understanding. When teachers are designing lessons, units, or courses, they often focus on the activities and instruction rather than the outputs of the instruction. Therefore, it can be stated that teachers often focus more on teaching rather than learning. This perspective can lead to the misconception that learning is the activity when, in fact, learning is derived from a careful consideration of the meaning of the activity.

As previously stated, backward design is beneficial to instructors because it innately encourages intentionality during the design process. It continually encourages the instructor to establish the purpose of doing something before implementing it into the curriculum. Therefore, backward design is an effective way of providing guidance for instruction and designing lessons, units, and courses. Once the learning goals, or desired results, have been identified, instructors will have an easier time developing assessments and instruction around grounded learning outcomes.

The incorporation of backward design also lends itself to transparent and explicit instruction. If the teacher has explicitly defined the learning goals of the course, then they have a better idea of what they want the students to get out of learning activities. Furthermore, if done thoroughly, it eliminates the possibility of doing certain activities and tasks for the sake of doing them. Every task and piece of instruction has a purpose that fits in with the overarching goals and goals of the course.

As the quote below highlights, teaching is not just about engaging students in content. It is also about ensuring students have the resources necessary to understand. Student learning and understanding can be gauged more accurately through a backward design approach since it leverages what students will need to know and understand during the design process in order to progress.

“In teaching students for understanding, we must grasp the key idea that we are coaches of their ability to play the ‘game’ of performing with understanding, not tellers of our understanding to them on the sidelines.”

The Three Stages of Backward Design

“Deliberate and focused instructional design requires us as teachers and curriculum writers to make an important shift in our thinking about the nature of our job. The shift involves thinking a great deal, first, about the specific learnings sought, and the evidence of such learnings, before thinking about what we, as the teacher, will do or provide in teaching and learning activities.”

Stage One – Identify Desired Results:

In the first stage, the instructor must consider the learning goals of the lesson, unit, or course. Wiggins and McTighe provide a useful process for establishing curricular priorities. They suggest that the instructor ask themselves the following three questions as they progressively focus in on the most valuable content:

What should participants hear, read, view, explore or otherwise encounter?

This knowledge is considered knowledge worth being familiar with. Information that fits within this question is the lowest priority content information that will be mentioned in the lesson, unit, or course.

What knowledge and skills should participants master?

The knowledge and skills at this substage are considered important to know and do. The information that fits within this question could be the facts, concepts, principles, processes, strategies, and methods students should know when they leave the course.

What are big ideas and important understandings participants should retain?

The big ideas and important understandings are referred to as enduring understandings because these are the ideas that instructors want students to remember sometime after they’ve completed the course.

The figure above illustrates the three ideas. The first question listed above has instructors consider the knowledge that is worth being familiar with which is the largest circle, meaning it entails the most information. The second question above allows the instructor to focus on more important knowledge, the knowledge and skills that are important to know and do. Finally, with the third question, instructors begin to detail the enduring understandings, overarching learning goals, and big ideas that students should retain. By answering the three questions presented at this stage, instructors will be able to determine the best content for the course. Furthermore, the answers to question #3 regarding enduring understandings can be adapted to form concrete, specific learning goals for the students; thus, identifying the desired results that instructors want their students to achieve.

Stage Two – Determine Acceptable Evidence:

The second stage of backward design has instructors consider the assessments and performance tasks students will complete in order to demonstrate evidence of understanding and learning. In the previous stage, the instructor pinpointed the learning goals of the course. Therefore, they will have a clearer vision of what evidence students can provide to show they have achieved or have started to attain the goals of the course. Consider the following two questions at this stage:

- How will I know if students have achieved the desired results?

- What will I accept as evidence of student understanding and proficiency?

At this stage it is important to consider a wide range of assessment methods in order to ensure that students are being assess over the goals the instructor wants students to attain. Sometimes, the assessments do not match the learning goals, and it becomes a frustrating experience for students and instructors. Use the list below to help brainstorm assessment methods for the learning goals of the course.

- Term papers.

- Short-answer quizzes.

- Free-response questions.

- Homework assignments.

- Lab projects.

- Practice problems.

- Group projects.

- Among many others…

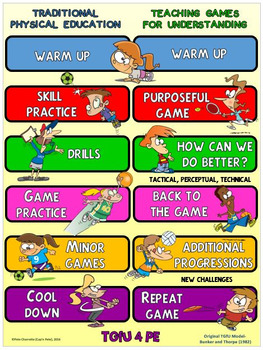

Traditional Model Vs Teaching Games For Understanding Kids

Stage Three – Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction:

The final stage of backward design is when instructors begin to consider how they will teach. This is when instructional strategies and learning activities should be created. With the learning goals and assessment methods established, the instructor will have a clearer vision of which strategies would work best to provide students with the resources and information necessary to attain the goals of the course. Consider the questions below:

Traditional Model Vs Teaching Games For Understanding Money

- What enabling knowledge (facts, concepts, principles) and skills (processes, procedures, strategies) will students need in order to perform effectively and achieve desired results?

- What activities will equip students with the needed knowledge and skills?

- What will need to be taught and coached, and how should it best be taught, in light of performance goals?

- What materials and resources are best suited to accomplish these goals?

Leverage the various instructional strategies listed below:

The Backward Design Template

A link to the blank backward design template is provided here (https://jaymctighe.com/resources/), and it is referred to as UbD Template 2.0. The older version (version 1.0) can also be downloaded at that site as well as other resources relevant to Understanding by Design. The template walks individuals through the stages of backward design. However, if you are need of the template with descriptions of each section, please see the table below. There is also a link to the document containing the template with descriptions provided below and can be downloaded for free.

Backward Design Template with Descriptions (click link for template with descriptions).

References

- Sample, Mark. (2011). Teaching for Enduring Understanding. Retrieved from http://www.chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/teaching-for-enduring-understanding/35243.

- Wiggins, Grant, and McTighe, Jay. (1998). Backward Design. In Understanding by Design (pp. 13-34). ASCD.

This teaching guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.